Hello, dear readers. This week, we’ll be discussing the status of provisional admission offered by the Joint Admissions and Matriculation Board (JAMB).

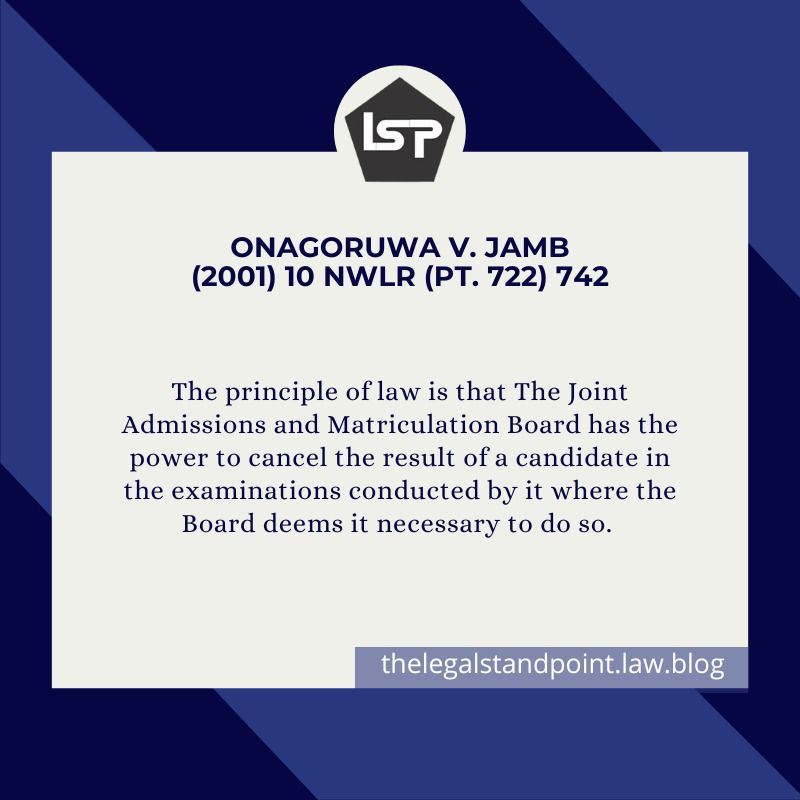

In Onagoruwa v JAMB (2001) 10 NWLR (Pt. 722), the appellant sat for the 1993/94 JAMB examination and ‘successfully’ passed. As a result, he received a letter of provisional admission to pursue a first-degree program in Electrical Engineering at the University of Ilorin. He accepted the offer, registered, and began his studies. However, the situation took an unexpected turn when JAMB informed the University that it had cancelled the appellant’s exam results and urged the institution to withdraw Onagoruwa’s admission.

Feeling aggrieved, the appellant took legal action against JAMB at the Federal High Court, seeking declaratory reliefs, an injunction to continue his studies, and N5 million in damages. Initially, the court granted an interlocutory injunction that allowed him to continue his studies while the case was being decided. However, JAMB defended its actions by explaining that after the initial release of the examination results, they conducted a post-exam review of 401,791 candidates. Among these, 1,706 candidates, including the appellant, were found to have discrepancies in their marks, leading to the cancellation of their results and subsequent withdrawal of their provisional admissions.

Further complicating the case, it was noted that the appellant did not contest the defense’s claim that his original score was inaccurate. During cross-examination, evidence was presented showing that the score indicated on his notification of results as 214 was incorrect and that his actual score was 112. This lower score was not enough to secure him admission on merit.

Since the principle of law, as held in Pascutto v Adecentro (Nig.) Limited (1997) 11 NWLR (Pt.529) 467 is that where evidence given by a party to any proceedings was not challenged by the other party who had opportunity to do so, it is open to the court seized of the matter to act on such unchallenged evidence before it, and owing to that fact that the appellant did not challenge this evidence, the court acted on it.

In addition, the trial court, after considering the evidence, dismissed the appellant’s claims entirely. Dissatisfied with the outcome, the appellant took the matter to the Court of Appeal. One of the issues for determinations during the appeal was the nature of a valid contract. For a contract to be binding, there must be a mutual understanding and agreement between the parties involved. In this case, JAMB argued that the post-examination review revealed that the appellant did not meet the minimum entry requirements for admission. Therefore, there was no valid contract between him and the University since the conditions for a final admission were not fulfilled.

Furthermore, Section 5 of Joint Admissions and Matriculation Board Act empowers the authority to regulate admissions into Nigerian tertiary institutions, including the power to cancel results. While JAMB can cancel a candidate’s results, this power must be exercised fairly and justly, without any form of arbitrariness. The court examined whether JAMB had acted within its rights and found that the cancellation of the appellant’s results was within their legal authority

A significant aspect of this case centered around the meaning of “provisional” in the context of the admission letter issued by JAMB. The term “provisional” is defined as something temporary, preliminary, or tentative. In legal terms, it implies that the offer of admission is not final and may be withdrawn if certain conditions are not met. In the appellant’s case, the court held that since the admission was provisional, JAMB was within its rights to rescind it upon discovering the discrepancies in his examination results.

Finally, the court addressed the duty of a party seeking declaratory relief. It emphasized that the burden is on the claimant to present evidence proving their entitlement to such relief. In this instance, the appellant failed to provide evidence to support his claim that he was not involved in any examination malpractice, leading the court to deny the declaratory relief he sought.

Moving on, I think while the court’s decision that the appellant should prove that he did not engage in exam malpractice is legally sound, practically achieving this is incredibly challenging. How would one gather evidence to prove that especially in such a scenario? Would the appellant have to call his exam seatmates as witnesses or request CCTV footage? Even then, JAMB controls such footage, and what happens in rural centers where CCTV wasn’t used? These practical hurdles make discharging the burden of proof an onerous task. In the Onagoruwa’s case, it seems the appellant lost because he may have indeed been involved in exam malpractice. Otherwise, why didn’t he challenge the evidence against him? The lack of a challenge raises questions and implies that the appellant might not have been entirely innocent.

In conclusion, Onagoruwa’s case underscores the temporary nature of provisional admissions and the significant power JAMB holds in ensuring that only candidates who meet all criteria are granted final admission into Nigerian universities