People often consider their names important to them and many may wish for exclusivity, believing their name should be uniquely theirs. However, in Nigeria, the law does not grant anyone the sole right to a personal name. No matter how significant a name may be to an individual, the principle of law is that it cannot be owned or restricted to one person.

In the case of Offoboche v. Offoboche (2006) 13 NWLR (Pt. 997) 298, the issue of monopoly of names came up for determination. In that case, the appellant claimed that the respondent was falsely presenting himself as his son and using his name. The appellant insisted that there was no biological, foster, or adopted relationship between them. In 1992, he asked his lawyers to send a letter to the respondent, urging him to stop this behaviour. When the respondent ignored the letter, the appellant published a disclaimer in a newspaper in 1998, but the respondent continued to use the appellant’s name.

As a result, the appellant filed a lawsuit seeking a declaration that the respondent was not his son and requested an order for him to stop using his name. The respondent responded by asking the court to dismiss the case, arguing that it was unjustifiable and an abuse of process. The trial court ruled that the respondent was not related to the appellant but denied the request to prevent him from using the name, stating that he had the right to choose any name he wanted.

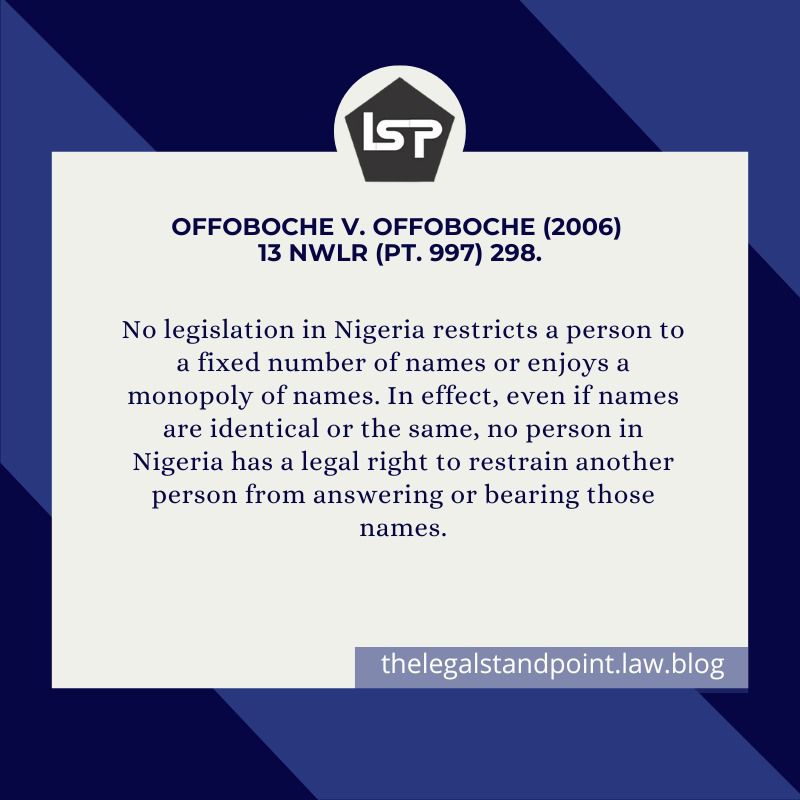

Dissatisfied with this decision, the appellant appealed to the Court of Appeal, arguing that the trial court’s conclusion about the respondent’s right to bear his name was unjustified. At the Court of Appeal, the main issue for determination was whether there is right to monopoly of names. Resolving this issue against the appellant, the court per Ibiyeye JCA opined that: ‘No legislation in Nigeria restricts a person to a fixed number of names or enjoys a monopoly of names. In effect, even if names are identical or the same, no person in Nigeria has a legal right to restrain another person from answering or bearing those names. In the instant case, the appellant was only creating a dispute where there was none. This was so because the respondent had cautiously decided not to contest the use of the names that appeared very dear to the appellant with him.’

In addition, the Court also held that ‘no person, group of persons or family has a monopoly of names. Persons have unrestrained liberty to pick and choose names that please them’. Similarly in Alliance for Democracy v. Fayose and Ors (2005) 10 NWLR (Pt. 932) 151, Nsofor JCA stated that ‘Of what concern or to whom does it matter if “A” chooses to be called or known by many, or very many names’ I confess that I know of no legislation or a Decree in Nigeria restricting any person(s) to a number of names he may be called or known by. No such law!’

Nevertheless, it is instructive to note that in law, persons are generally subdivided into two: juristic entities and natural persons. While the principle in Offoboche’s case resonates with the former, it doesn’t apply to the latter. This is because the law ensures that corporate names are distinct from one another to avoid deception. Specifically, Section 852(1)(a) of the Company and Allied Matters Act 2020 forbids identical names. Similarly, this principle of law has also received judicial approval in the popular case of Niger Chemists Limited v. Nigeria Chemists 7 (1961) ANLR 180 which is reiterated in the 2024 recent case of A. Dikko & Sons Ltd. v. C.A.C. (2024) 8 NWLR (Pt. 1939) 75.

In conclusion, everybody gather dey, lol. you no fit say person you dey bear Jumoke make others no bear ham. Thank you for reading.❤️ See you next week🙏